In 1995 the Barings bank completely collapsed, but how did this happen? In this article Wout will tell you more about the person responsible.

When looking back at 2016, one can only agree that some major events happened that took a different path than expected. In November 2016 about 129 million United States’ citizens casted their vote for the presidential elections. Although most polls predicted differently, giving Hillary Clinton on average about 3.2 percentage points difference ahead of her opponent[1], the republican Donald Trump was elected as the 45th president of the United States. About five months earlier, in June, the United Kingdom’s population unexpectedly voted in favour of the so-called Brexit, a withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union. It is an incident that the European Union has never seen since the start of the European Economic Community in 1958 and, therefore, the European Union is unacquainted with dealing with it. 2016 also showed a significant increase in the support for populist parties in many European countries. Right-wing populist parties have been expanding in polls, such as the Alternative für Deutsland (Petry) in Germany, Front National (Le Pen) in France and Partij voor de Vrijheid (Wilders) in the Netherlands. With elections upcoming in 2017 in these three countries, their role will be of major importance. Although these events may seem unrelated at first, a common factor can be distinguished: globalisation.

Globalisation

The American choice for Trump, a vote against the European Union and the increase in support for strong right-wing parties may be attributed to the growing discontent of the many individuals that feel disadvantaged by the ongoing rise in globalisation which, subsequently, has led income inequality to rise. Up till now the silent majority has not benefited from international trade – or not as much as the top-income earners did. Some have lost their job due to globalisation, have not seen significant increases in real incomes or have seen greedy bosses take up the largest gains of international trade. This group is becoming increasingly assertive in opposing the current levels of income inequality and, therefore, have felt the appeal of voting against the establishment.

“Economic theory predicts that income inequality in the western world will rise over time.”

Economic theory

Numerous economic models have been designed to describe the effects of increased globalisation on major economic variables. The most well-known models of international trade[2] predict that people with labour-intensive, low-skilled jobs in the western world will indeed be adversely affected by increased globalisation. Those jobs are likely to be off-shored, i.e. they will be moved towards emerging countries where wages and production costs are lower. The low-skilled labour force in these emerging or developing countries, which represents a particularly large fraction of the total labour force in these economies, will benefit from this outsourcing. In the western world, high-skilled or capital-intensive jobs will typically gain from more trade. Consequently, economic theory predicts that income inequality in the western world will rise over time.

Empirical observations

In accordance with economic models of international trade it has indeed been found that low-skilled workers faced substantial declines in their real wages[3]. Moreover, two trends that go hand in hand have emerged in the last 50 years. Wage polarization, which refers to the gradual increase in wages of low- and high-skilled jobs at the expense of middle-skilled ones, led to an increase in income inequality. This wage polarization may have its grounds in job polarization, which entails that especially middle-skilled rather than low-skilled workers are the ones that lose from international trade in terms of job availability. The intuition is that consumer-interactive tasks performed by low-skilled workers, such as haircuts and taxi services, cannot easily be outsourced to other counties[4]. These activities are location specific. Moreover, routine tasks performed by middle-skilled workers can be split more easily and are therefore more prone to offshoring. Job polarization implies that low- and high-skilled jobs have become more attractive, thereby increasing their wages, at the expense of the middle-class.

The elephant graph

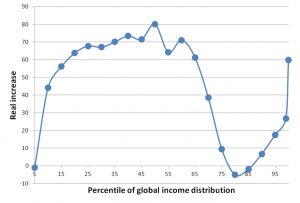

The findings of Milanovic (2012), who calculated the changes in real incomes between 1988 and 2008 for the global income distribution (in 2005 international dollars), have some overlap with job and wage polarization. The period under consideration is of special interest as deregulation and market-based reforms took off and, consequently, globalisation as well. When depicted in a figure, it resulted in the so-called elephant graph (Figure 1). It is a clear visual representation of the winners and losers of globalization. The largest gains of globalisation flow to the middle class of the emerging economies. Large parts of the populations from China, India, Indonesia, Brazil and Egypt are located around this median income, where increases up to 80% have been attained. The top 1% of the global income distribution, which typically consists of the very rich in the western world, has no reason to complain either as their incomes have increased by about 60%. The bottom one third, except for the poorest 5%, has also seen significant increases in their real incomes. This might be due to the large reduction in poverty that has been achieved as part of the Millennium Development Goals. As of 1990, in only twenty years, about 1 billion people have been lifted out of poverty. A reason why the poorest 5% has not benefited from globalisation could be that those people are really difficult to reach. The provision of aid to them might be impossible or ineffective.

The most relevant part of the elephant curve to the interpretation of why people voted for Trump, for the Brexit and support right-wing populist parties to a larger degree, is the 75th till 90th percentile. This global upper class largely consists of citizens in rich countries and former communistic ones. These people have not benefitted at all from the increase in globalisation while so many people not only have, but also to a significant extent. This discrepancy resulted in an increase in income inequality in the developed world.

Figure 1. The ‘Elephant Graph’: increases in real incomes between 1988 and 2008 for the world population.

Source: Milanovic (2012), Global Income Inequality by the Numbers: in History and Now.

Gini-coefficient

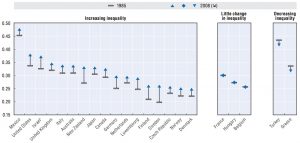

A different but commonly used and well-known measure of income inequality is the Gini-coefficient, which measures the extent to which the distribution of income within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. It ranges from zero, where everybody earns the same income, to one, where all income goes to a single person. From an OECD sample it follows that 17 out of 22 countries faced a substantial increase in their Gini-coefficients between 1985 and 2008, while only 2 countries saw their Gini-coefficients drop. The Gini-coefficient in 1985 stood at an average of 0.29, from which it increased by almost 10% to 0.32 in 2008. Clearly, income inequality in the developed world has been rising since the mid 1980s, which corresponds to the same period in which globalisation took off.

Figure 2. Gini-coefficients of 22 OECD countries (1985 and 2008).

Source: OECD (2011), An Overview of Growing Income Inequalities in OECD Countries: Main Findings.

Solution

The losers, or at least non-winners, of globalisation are the ones that increasingly take a different viewpoint on contemporary developments and show these concerns in the political landscape. Currently, some policy makers and politicians try to address these concerns by falling back on the ideology of protectionism, that generally has seen an ever-reducing support since Adam Smith’s publication of the Wealth of Nations. In practice, this tendency is being expressed via cancelling trade agreements (TPP and probably TTIP as well), threatening to raise import tariffs to protect one’s economy, the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European common market and the threat of stepping out of the Eurozone.

“Western governments will have to distribute the gains of international trade more equally among their populations.”

This change in direction is not only highly unwanted to the very rich in the western world, but to all. When globalisation is reduced, it will lead to a reduction in total welfare. Overall, citizens in developed countries will have less to spend when tariff and non-tariff barriers are reintroduced, when trade routes are closed and when trade agreements are cancelled. Deliberately giving up some part of potential welfare is undesirable and, foremost, unnecessary. Western governments will have to distribute the gains of international trade more equally among their populations. This implies that the top of the income distribution will face slower increases in their real incomes, that were caused by globalisation, than they have been used to. Governments have got many policies at their disposal. One can roughly distinguish two kinds of policies: (1) policies that specifically aim at those negatively affected by international trade and (2) policies that more generally try to reduce income inequality. The first would be more appropriate but is at the same time more difficult to design. Think of providing extra retraining and schooling programs for workers that have likely lost their job because of globalisation, like some blue-collar workers. A policy that reduces income inequality in general, and therefore being less precise, would be a reform of a government’s tax system, for instance by increasing income taxes for the very rich. Creative and careful analysis of policies will have to be done to make sure that they address the problem at hand. To conclude, in answering the needs and concerns of an increasing part of the population in the developed world politicians and policy makers would do best by ignoring the tendency to move towards protectionism and by focussing on a better redistribution of the gains of globalisation. It will be a step forward.

[1] Retrieved from www.realclearpolitics.com

[2] The model of absolute advantages (Adam Smith), the model of comparative advantages (David Ricardo) and the Heckscher-Ohlin model, also referred to as the factor-proportions theory

[3] For instance, Acemoglu and Autor (2010)

[4] Oldenski (2012)

In 1995 the Barings bank completely collapsed, but how did this happen? In this article Wout will tell you more about the person responsible.

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the logistics of education. In this article, Daniël writes about the stress that comes with online education.

In this article, Boris de Bie and Sjors Seinen describe their experience with the CFA track of the master Finance, and the preparation for the CFA exam.

Curious about how Tilburg University will spend its money on the quality of education in the coming years? Read it in this article!